The National Institutes of Health (NIH) currently comprises 21 distinct institutes, each representing a major health concern — from cancer and cardiovascular disease to mental illness, infectious conditions, and diabetes. These institutes reflect the seriousness and national priority of these conditions. However, one major disease that is intricately connected to many of them remains conspicuously absent: obesity.

A Historical Look at Public Health Prioritization

When the National Cancer Institute was established in 1937, it signaled the government’s recognition of cancer as a critical public health threat. Decades of research and investment followed, revolutionizing our understanding of cancer’s underlying mechanisms, developing effective screening protocols, and producing advanced treatments that now significantly reduce mortality. Breast cancer deaths, for example, have plummeted by 58% since the 1970s — a direct outcome of coordinated research, early detection, and treatment efforts.

Similarly, the National Heart Institute, now known as the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), was created in 1948. This led to groundbreaking medical advancements such as angioplasty, coronary artery bypass surgery, and the development of cholesterol-lowering and blood pressure medications. These interventions, aimed at both prevention and management, have dramatically reduced deaths from heart disease — by nearly 67.5% between 1969 and 2013.

Given these precedents, one must ask: Isn’t it time obesity received the same level of focus, research, and institutional support?

Obesity by the Numbers: More Prevalent Than Cancer or Heart Disease

Historically, new NIH institutes have been formed based on a combination of disease prevalence, impact, and national urgency. By all three metrics, obesity more than qualifies.

- The lifetime risk of cancer in the U.S. is about 38.9%

- Cardiovascular disease affects around 9.9% of adults over 20

- In contrast, obesity affects 40.3% of American adults — and this number soars to 73.6% when we include individuals with overweight

In other words, nearly 3 out of every 4 adults in the U.S. are living with excess weight, many of whom are experiencing or will develop metabolic diseases that stem from it. This isn’t just a medical issue — it’s a national health crisis hiding in plain sight.

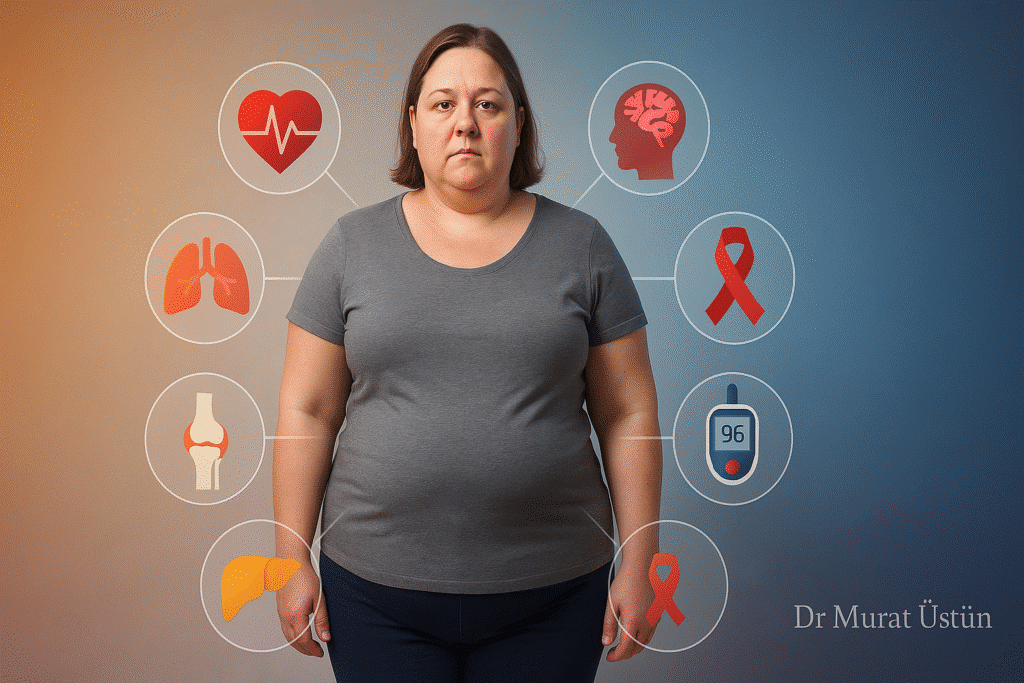

The Far-Reaching Impact of Obesity

Obesity is not a siloed disease. It either causes or contributes to over 20 serious medical conditions. According to recent research led by Johns Hopkins, obesity was found to have strong links with 16 specific diseases, with the risk increasing alongside the severity of obesity. These include:

- Cardiometabolic Conditions: hypertension, type 2 diabetes, high cholesterol, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

- Kidney and Liver Issues: chronic kidney disease, metabolic steatotic liver disease (MASLD)

- Respiratory Disorders: obstructive sleep apnea, asthma

- Vascular Complications: pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis

- Digestive and Musculoskeletal Problems: biliary stones, GERD (reflux), and osteoarthritis

- Gout and Other Inflammatory Conditions

In terms of sheer financial impact, the numbers are staggering. Between 2014 and 2018, the economic burden of obesity in the U.S. surpassed $1.4 trillion, factoring in both direct medical expenses and indirect consequences like lost productivity and disability. These aren’t just healthcare system costs — they’re lost years of healthy life and economic potential.

Why Obesity Deserves a National Priority

Health isn’t simply a personal matter — it’s a public priority, and nowhere is this more evident than in the obesity epidemic. Over 200 million Americans are now living with overweight or obesity. This widespread prevalence gives us not only the urgency but also the collective power to demand better from our public health systems.

What’s needed is greater transparency, stronger research, and a clear public communication strategy. We must understand how environmental triggers — such as poor nutrition, sedentary work environments, chronic stress, and exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals — interact with biological and genetic factors. Only then can we develop tailored, effective, and compassionate strategies to combat obesity.

A “Stepchild” Condition

Currently, obesity is tucked under the jurisdiction of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), where it receives some attention through the NIH Obesity Research Task Force. Other NIH institutes approach obesity only in relation to their primary focus — for example, the NHLBI investigates how obesity affects heart health, not obesity itself.

This fragmented approach is in sharp contrast to the holistic strategies that have made such a difference in cancer and heart disease outcomes. Despite obesity meeting the historical benchmarks for its own NIH institute, it remains underprioritized and underfunded.

We Don’t Need More Bureaucracy — We Need More Commitment

Creating a separate National Institute of Obesity would certainly elevate the condition’s visibility. But the core need isn’t just about creating another institute — it’s about committing real resources and strategic focus to prevention, early diagnosis, and effective treatment.

We need a public health approach that matches the scale and complexity of the problem — not just from researchers and clinicians, but from lawmakers, public health leaders, and healthcare institutions.

We must shift the narrative away from blame and shame toward evidence-based care and systemic solutions. Just as we made cancer and heart disease national priorities, it’s time to make obesity one too.

Final Thoughts

Obesity is no longer a silent epidemic. It is a loud and urgent public health emergency — one that is deeply intertwined with many of the diseases we’ve already committed to fighting. The case for prioritizing obesity is not only compelling — it’s overdue. By viewing obesity not just as an individual issue but as a national crisis, we open the door to meaningful change — from better treatment options to healthier environments and a more informed public.

Let’s not wait another decade to act.